Sorting Lists For Humans

I like humans. Many of my friends a humans; my wife is a human. And I admire their ability to arbitrarily order items in a list. Applying a manual order to a list of items has been discussed a few times on the Cassandra user list. And I’ve been thinking about it recently.

To keep things simple let’s start with an artificially constrained problem. Our list will only contain 50 “things” that must be manually sorted. The things consist of an Integer id and an ASCII label. We can also say that the rate of changes is not excessive. In this scenario there are two issues we want to look at:

- How do I move an item without re-ordering everything?

- How do I handle concurrent changes to the list?

The Natural Order

My first instinct is to duplicate the list order in Cassandra Columns. For example we could use a Composite Column name such as (weight, id). Cassandra would then sort the Columns by weight, using id as a tie breaker for duplicate weight’s. To get the list in order we simply select the Columns from the row.

Moving items using this data model can be painful. Consider the (weight, id) list below:

(1, 101)

(2, 102)

(3, 103)

(4, 104)

(5, 105)

If we want to move item 105 to be before item 102 we would change it’s weight to 2. To avoid duplicate weights we would then change the weight of 3 and the items that follow it. The reason to avoid duplicate weight’s is that the sort order for duplicates would be based on the id. If we had a better tie breaker duplicate weights would not be a problem.

The unceasing March Of Time is a handy tie breaker. With it we can say that if two items have the same weight the most recently updated one should be ordered last. If there are items with duplicate (weight, timestamp) values we can then use the id to break the tie. To avoid confusion with the Timestamp Cassandra stores for Columns I’ll refer to our timestamp as the ‘sequence’ or ‘seq’.

Using the weights and sequence model the Column names wil have the form (weight, seq, id). If we initialise the weight and seq to the current time stamp our example from above may now look like:

(1, 1, 101)

(2, 2, 102)

(3, 3, 103)

(4, 4, 104)

(5, 5, 105)

To move an item so that it preceeds another we:

- Set the

weightto the moving item of the weight of the new following sibling -1. - Set the

seqof the moving item to the current timestamp.

After moving item 105 to preceed item 102 the list would look like:

(1, 1, 101)

(1, 6, 105) # items with duplicate weight sorted on seq

(2, 2, 102)

(3, 3, 103)

(4, 4, 104)

We were able to move item 105 without having to change any other items in the list. And it almost looks like we did it just by chaning one value. However we cannot change column names in Cassandra, we can only create and delete them. This read-modify-write pattern has serious implications when it comes to concurrent changes as we’ll see later. Until then let’s implement the current design.

To store natually sorted lists in Cassandra start with a cassandra-cli schema:

To load and modify the list using Python and pycassa:

Note that the move() function deletes the old column before inserting the new one.

To exercise the code I first called initialise() to fill the list and used get() to view it. I then called move() to place item 5 before 2. When item 4 is moved to be before 2 it is given then same weight as 5 but a higher seq. This places 4 after 5 and both of them before 2:

We moved the item but it was not pretty; we moved it by deleting and then re-inserting. If our read-modify-write operation for item 5 overlaped with another client moving 5 it would result in two entries for 5. In a tradtional RDBMS we could prevent this by running an ACID Transaction working at Repeatable Read or better. But this is Sparta / Cassandra (cross out as applicable) and we don’t have locking transactions.

The timeless wonder of the whole thing

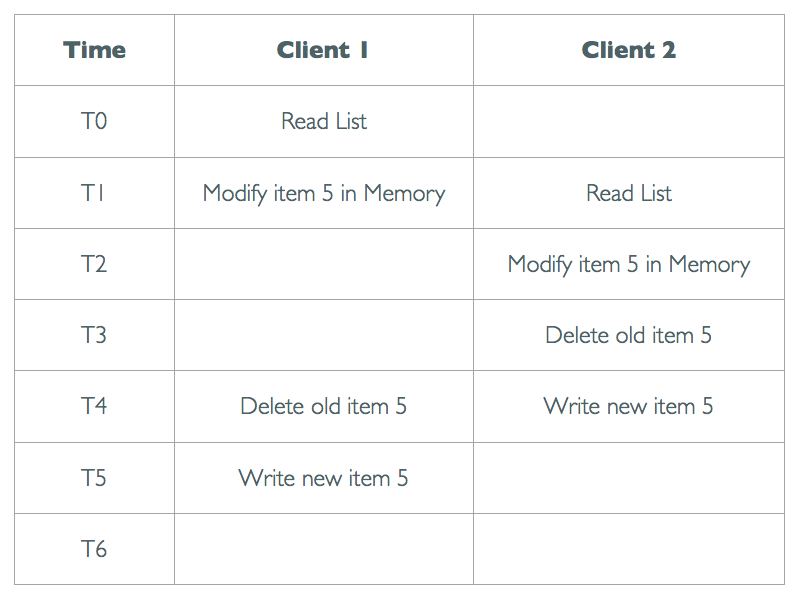

The overlapping operations we are trying to avoid look like this:

If the Clients used a REPEATABLE READ Transaction around all their work they would block each other. The Shared locks taken when reading would prevent the other Client from obtaining the Exclusive lock needed to delete. The DB Engine would pick an victim and ABORT it’s Transaction.

A Transaction around the Delete and Write calls would work. The Delete from Client 1 would be blocked until Client 2 completed. Client 1 could then notice it’s Delete updated 0 rows and ABORT it’s own Transaction.

The locks taken in the Transaction would prevent the Clients from modifying the same data. This is known as serializability and is the purpose of Transactions:

…a transaction schedule is serializable if its outcome (e.g., the resulting database state) is equal to the outcome of its transactions executed serially, i.e., sequentially without overlapping in time.

I can think of two approaches to making our move() operations super cereal. The first is to make the Cassandra requests inherently serialisable. The second is to record the move() transformations and have the application apply them in a serial fashion.

Take It and Turn It

At the start of the post I restricted the problem to lists of 50 “things”. I chose 50 for no particular reason. So instead of 50 let’s say lists where it’s reasonable to read all of the items at once. Even if you don’t want to display all of the items. To get idea of what is reasonable, I can read 50 Columns that are 50 bytes long from a hot row cache in about 260 Microseconds (excluding network IO).

While we are at it lets say it’s unnecessary to have Cassandra maintain the order of the items in the list. It won’t take much effort for the client to sort them. So lets see what happens when we give up the ability to ask the database for exactly the right data in the correct order.

The weight, seq and label for items in the Read Sorted list will be stored in Column values. While the Column names will contain the item_id and a property name:

To move an item we update it’s weight and seq Columns, and because they are column values we do not need to delete first. Row Level Isolation ensures that reading clients see either all updates or none. Overlapping requests from clients that update the same row will be serialised by the server. And the Column Timestamp included in the request means that the order they are applied in does not matter. Moving an item is now an atomic and serialisable operation.

Read Sorted lists are implemented by the Python code:

Note that move() now makes a single insert call.

I exercised the code using the same steps as above:

The output from the cassandra-cli shows that the order of the Columns does not change when items are moved.

Ledger List

It’s time to start adding functionality, and complexity. The Ledger List maintains the order of items in Cassandra Columns, so uses a delete and insert for moving. The move operations are written to an application Transaction Log rather then applied directly to the list. When a client reads the list it applies the current transactions to it’s client local copy; a process that is inherently serializable. Updates to the list stored in Cassandra are done through background worker processes which can be syncronised at the application level. The Data Model is roughly the same as Natural Lists so lets start there.

Each item will usually be represented by one column in a row in the LedgerList Column Family. The column name will be a composite of weight, seq, item_id and deleted. The column value will be used to store the item label. The deleted component is used to soft delete an item in the list when applying a Transaction. When an item is soft deleted a new column is created with the same (weight, seq, item_id) that has deleted set to True. Transactions are serialised as JSON and stored in a single column where the column name is the Transaction ID:

The move() function creates a Transaction and stores it in the LedgerTransactions Column Family. When get() reads the list it applies the Transactions to it’s local copy. Later a background process can call apply_tx() to update the list in Cassandra. While both get() and apply_tx() move items their implementation is very different.

apply_tx() has a tough life; to move an item it must delete the old column and insert a new one. It needs to make sure that Clients see either the state before the move or after it. But the Row Level Isolation guarantee used previously cannot be relied on, as it only applies to a single row mutation. And deleting and inserting columns for the same row must be done with two mutations. So our approach cannot rely on a delete and an insert being processed together.

To apply a Transaction to the list in Cassandra we:

- Soft delete the old item and insert the new one by inserting new columns.

- Hard delete the old item and the soft delete marker.

- Hard delete the Transaction.

Once the insert in step 1 has completed was can consider the Transaction “in flight” until step 3 completes. During this time there may be three columns in the row that identify the item we are moving. The original entry will still be there with it’s original weight and seq. A soft delete column will be there with the same weight and seq as the original, but marked as deleted. And finally a second non deleted column will be there placing the item at it’s new position. After step 3 the Transaction has been deleted and there will only be a single column for the item again. Reads that take place while a Transaction is in flight have to account for the intermediate state they are seeing.

When get() reads the list it has to apply all the Transactions to it’s local copy, excluding those that are in flight. For each Transaction record it:

- Checks if the item being moved has been soft deleted. If so the Transaction is in flight (after step 1 in

apply_tx()) and can be skipped. - Tries to remove the item being moved from it’s local copy. If the item is missing the Transaction is still in flight (between steps 2 and 3 in

apply_tx()) and can be skipped. - Inserts the item at the new location.

- Filters to remove soft deletes left by step 1.

- Sorts the list.

Ledger Lists are implemented by the Python code below which includes some diagnostic print statements:

To exercise the code I used the ISO list of countries found in the gist that contains the sample code. First the list was initialised and a couple of countries moved:

Note that when an item is moved the row in the LedgerList Column Family does not change.

Next I ran apply_tx() and passed a flag to stop processing after step 1. This places the Transaction in flight by inserting the soft delete for the old item and writing the new one. Log messages from get() show it detected the in flight Transaction and skipped processing:

A second call to apply_tx() had it re-process the in flight Transactions and stop at step 2. Log messages from get() show it detected the items had already been moved and skipped processing:

A final call to apply_tx() without any parameters processed the Transactions to completion. get() no longer has to apply Transactions:

What’s Missing ?

The next things to look at are pagination and adding more operations such as “add” and “delete”. It would also be handy to move items outside of the current page.

So far this is has been an experiment conducted on my couch, for fun. If you think I have missed something or got it wrong let me know.