Row Level Isolation and Consensus

Row Level Isolation in Cassandra 1.1 is the most important new feature in Cassandra so far. There have been a lot of great improvements since version 0.5, but row level isolation adds an entirely new feature. One that opens the door to new use cases.

But if you could just see the beauty

If you are not familiar with row level isolation Data Stax have a blog post on it. In addition I covered some of the implications in my Cassandra Summit 2012 talk on Query Performance.

To recap, row isolation leverage’s the “zero copy clone” feature of Snap Tree. This allows write threads in Cassandra to clone the current Memtable columns for a row and work on the cloned copy. Changes are then only applied to the Memtable if the row has not been updated while the write thread was working.

In my Cassandra Summit talk I replicated the logic as best I could using Commodore 64 basic:

00 REM Cassandra for C64

05 REM Clone row_cols into my_cols

10 GOSUB 1000

20 FOR col = write.first_col TO write.last_col

25 REM Add or Reconcile col with my_cols

30 GOSUB 2000

40 IF my_cols != row_cols THEN GOTO 05

50 NEXT col

55 REM Atomic swap row_cols with my_cols

60 GOSUB 3000

70 IF swapped_cols = FALSE THEN GOTO 05

At line 10 we clone the current Memtable columns for the row we want to update. Each column in the mutation is then reconciled against the my_cols copy, isolating the changes from the Memtable. After each column is added the code checks if the Memtable’s row_cols object has been replaced (line 40). If it has we jump back to 10 and try our changes again. A final check in the form of an atomic compareAndSet is done at line 60. Again if the Memtable row_cols has been replaced this write thread tries again.

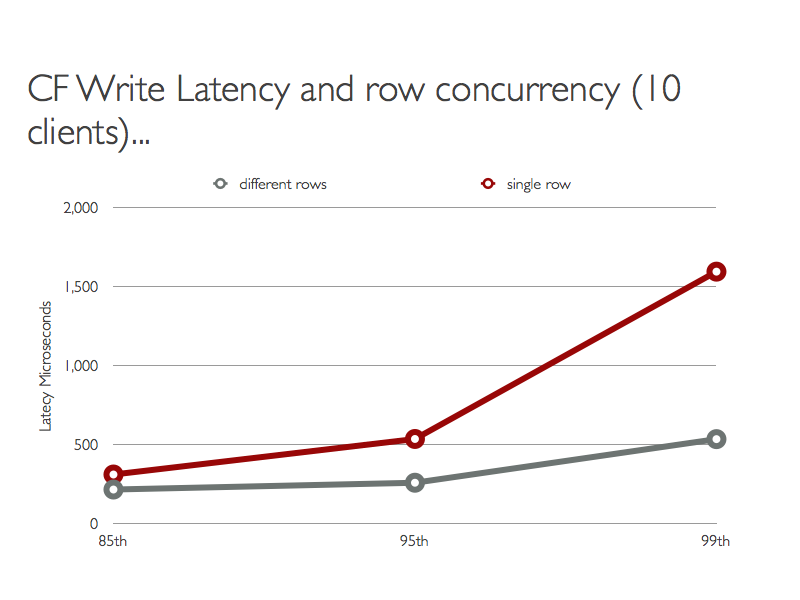

As a result readers will see either all or none of the changes applied by a writer. It also means that writer threads may take several attempts to complete their write. In my talk I looked at clients trying to write 10,000 (50 byte) Columns to a row in chunks of 50 columns. For the grey line below 10 clients wrote to different rows, for the red line they wrote to the same row.

There are some trade off’s. The increased latency is due to write threads detecting changes to the Memtable and restarting their operation. On the upside however we now have a database that provides lock free atomic assignment to multiple registers / values.

(AFAIK we cannot call this wait free as there is no guarantee that a particular write thread will complete given infinite number of steps. For example a client writing 1,000 columns may be continually stopped by clients writing 1 column.)

We Can All Agree on Consensus

Consensus is an interesting topic in distributed systems, and one I’m enjoying learning about from The Art of Multiprocessor Programming. It’s an excellent book, and the inspiration for this experiment. From page 100:

A consensus object provides a single method

decide(). Each thread calls thedecide()method with its input v at most once. The object’sdecide()method will return a value meeting the following conditions:

- consistent: all threads decide the same value.

- valid: the common decision value is some threads input.

A further restricted placed on the algorithm is that is wait free, and there for lock free.

A Consensus Protocol has a Consensus Number n that describes the maximum number of threads it provides consensus for. Obviously the simplest level of Consensus is between two threads, so lets look at a protocol with a Consensus Number of 2.

Assign23

2-Consensus with a “(2/3) array” is discussed in the book which credits the idea to Maurice Herlihy, Wait-Free Synchronisation, 1991 (in case you missed it Maurice Herlihy is one of the book authors). It is also discussed in the teaching slide deck for chapter 5. The (2/3) array is actually used to prove it’s impossible to implement (wait free, so lock free) 2-consensus using only atomic registers.

The Assign23 class from the book looks like this:

Assign23 wraps access to an array of three elements. It uses a lock via the synchronized keyword to allow a caller to atomically write 2 array elements at a time. It uses the same lock when providing read access to ensure reads are consistent. That is reads only see the state before two elements are updated or after. The effect is to isolate writes from reads.

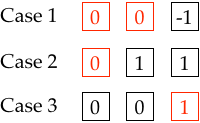

To build a 2-consensus protocol using Assign23 Threads write to elements in the array and then observe the state of the array. Each Thread (remember we only have 2) writes to 2 elements in the array. Thread 0 writes 1 to elements 0 and 1, while Thread 1 writes 1 to elements 1 and 2. To decide the outcome both Threads read part of the array. The consensus we are after is which Thread wrote to the array first.

Lets say we initialise an instance of Assign23 with -1 in all array elements. If Thread 0 writes and then reads from the array it will see three possible states:

From Thread 0s point of view it will decide:

- Case 1: Thread 0 wins. Thread 1 has not not written to the array.

- Case 2: Thread 0 wins. Thread 0 wrote first, then Thread 1.

- Case 3: Thread 1 wins. Thread 1 wrote first, then Thread 0.

The 2-consensus protocol is then constructed as:

Note that decide() does not tell you which thread wrote it’s value to the proposed array first. Or which made the call to assign() first. The Thread that is considered the winner is the one that acquired the lock (on the instance) implemented by the synchronized keyword.

CF23

So to implement Assign23 all we needed was atomic, isolated, read-write access to an array. Hmmm, I think we can do that in Cassandra.

Start with a Column Family definition using CQL3:

(Defining the column names up front is not necessary. It just makes the select statements below look nicer.)

The row key for the cf23 Column Family is the name of the Consensus object. The element_* columns represent the r array from Assign23, and the propose_* columns are the values proposed by the threads / clients.

To make the example easier let’s use Python and pycassa.

To use the Consensus2 class two clients needs to know the name of the consensus object they are sharing, and their client id. With that they can propose a value and agree on which value “won”.

In the examples below I ran two iPython clients and examined the database using cqlsh. In the first test player 1 answers the question first:

In the second test player 2 gets in first:

The Fine Print

Is this fair? Does the client who calls Cassandra first always win? No.

For example say the write thread for client 0 starts executing nanoseconds before the write for client 1. The first write thread may be pre-empted by the JVM before it gets a chance to complete, allowing the second thread to finish first. When the JVM resumes the first writer it will discover that the row columns have changed and re-apply it’s mutation. Unfortunately by then it’s too late, client 1 has won. A small “wall clock” advantage in starting a write is not enough to win. The race between the clients is the first to pass the GOSUB call at line 60 of our C64 code above.

This being Cassandra there is still a potential issue with timestamps and clock skew between clients. The value of element_1 in the cf23 row depends on the timestamps used by clients. If client 0 writes with a timestamp skewed to the future it’s write for element_1 may always win when reconciled with client 1. If this happened when client 0 wrote first, the array would look like Case 3 (from above) rather than Case 2. The result would be client 1 “winning” when really client 0 won.

In this situation CQL has an advantage over the RPC interface. If a TIMESTAMP is not included in an INSERT statement the coordinating node generates a timestamp for the new Columns. Baring NTP moving the clock backwards, successive calls to the same server should result in monotonic timestamps.

Finally you cannot reuse the Consensus2 object, the same is true for the in memory Java version in the book. If you do weird things happen: